Toward A Universal Suffrage > Women Activists: From Slavery to Suffrage

Women Activists: From Slavery to Suffrage

Marcy Church Terrell. Courtesy the Library of Congress.

“This is the story of a colored woman living in a white world. It cannot possibly be like a story written by a white woman. A white woman has only one handicap to overcome—that of sex. I have two—both sex and race.”

The roots of women’s suffrage in the United States are found in the movement to abolish slavery.

One of the reasons slavery was abolished and women gained the right to vote is because women asserted their right to organize, speak, and act on public and political issues.

“…it is the duty of woman, and the province of woman, to plead the cause of the oppressed in our land, and to do all that she can by her voice, and her pen, and her purse, and the influence of her example, to overthrow the horrible system of American slavery.”

Courtesy Mississippi Valley Traveler.

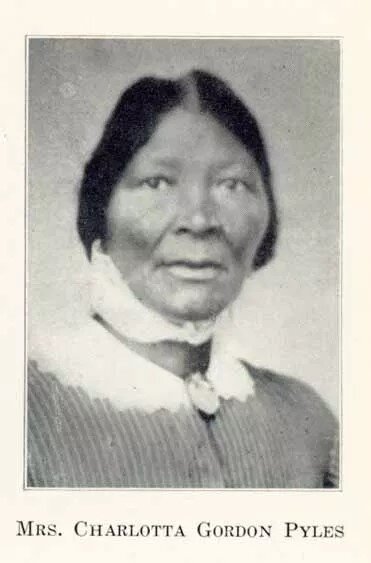

CHARLOTTA GORDON PYLES

ABOLITIONIST AND ADVOCATE

April 28, 1790 - January 19, 1880

Mrs. Pyles was born into slavery in Kentucky. In the 1850s, Mrs. Pyles and her family were freed after their plantation owner died and decided to move North. Tragically, one of her twelve children, a son, was kidnapped by the sons of the deceased plantation owner before the family could begin their journey. Mrs. Pyles also had two sons-in-law who remained enslaved.

Mrs. Pyles and her family were enroute to Minnesota when a harsh winter prevented them from completing their journey. They stopped in Keokuk, where the family settled permanently.

Once in Keokuk, Mrs. Pyles and her husband, Harry, were able to legally marry. Mr. and Mrs. Pyles made the painful decision to try and purchase the freedom of the sons-in-law rather than their own son because the sons-in-laws were needed to help support their families.

To purchase their freedom, Mrs. Pyles spoke in cities across the Eastern part of the United States. It is during this speaking tour and because of her advocacy that Mrs. Pyles reportedly met prominent abolitionist Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony, a leading women’s suffrage leader. In just six months, Mrs. Pyles was able to raise $3,000 to free her sons-in-law and bring them to Iowa. Mrs. Pyles wrote to her son explaining their decision and that he might find his way to freedom in the future. The family never heard from him again.

One of her children, Charlotta Smith, was an advocate as well. Mrs. Smith enrolled her son in school after winning a case in the Iowa Supreme Court to desegregate the school.

The Civil War and Voting Rights

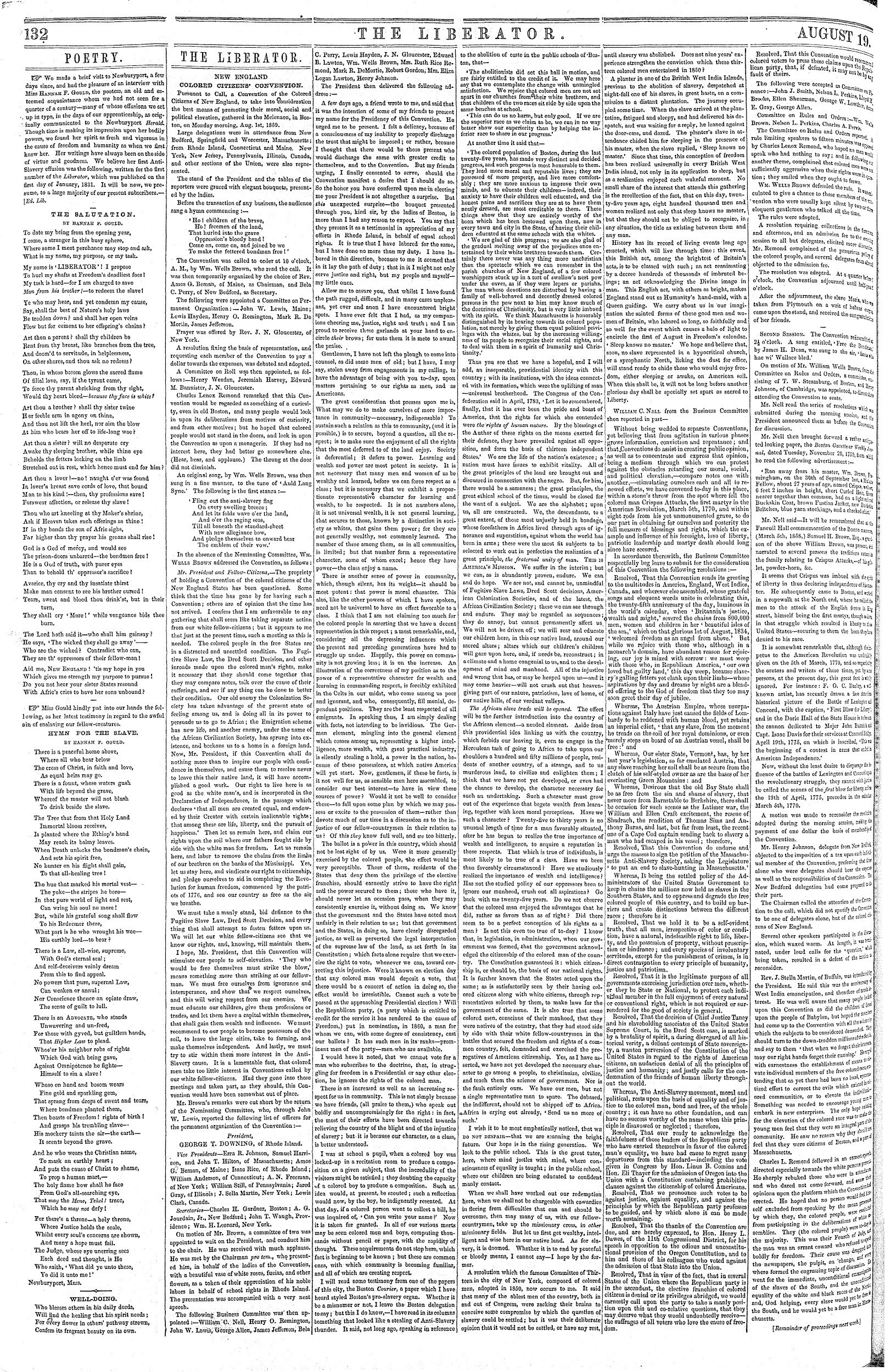

In 1859, the New England Convention of Colored Citizens demanded universal suffrage—that all women, Black and white, and Black men be given the vote. It would take more than 100 years for universal suffrage to become law throughout the United States.

Resolutions of the 1859 New England Convention of Colored Citizens were published in the Liberator, a weekly abolitionist newspaper. Courtesy the Liberator Files.

Following the Civil War, the public debated a new amendment to the US Constitution to address voting rights. Many suffragists wanted to guarantee voting rights for African American men and for all women. The 15th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified in 1870. It states that the right to vote cannot be denied due to “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” It was interpreted to apply only to men.

While African American women suffragists wanted the vote, many supported the effort to give the vote to Black men. The experience of being enslaved made it critical to survival that African Americans have the vote in some way.

African American women never abandoned the goal of universal suffrage. After African American men won the vote, the women (and some men) continued to work for women’s suffrage.

Race and the Women’s Suffrage Movement

The 15th Amendment. Courtesy of National Archives.

All women suffragists had to overcome sexism to gain the vote. African American women had to overcome racism as well.

After the 15th Amendment was ratified, some suffragists favored a Constitutional amendment, which would apply to all women. Others wanted to work for expansion at the state level, so states could keep in place other voting laws that upheld white supremacy.

Mobilizing to Win the Vote

Meeting of the Iowa Association of Colored Women's Clubs Davenport, May 1903. Courtesy the State Historical Society of Iowa.

African American women joined women’s organizations with white women. The white women in the organizations discriminated against African American members, promoted segregation rhetoric, and failed to speak out on issues critical to African Americans such as lynching. This led African American women to begin their own organizations that would value the experiences of African American communities.

Several of the most prominent were the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, National Association of Colored Women (NACW) and the Women’s Convention. These organizations had hundreds of thousands of members and were organized at the national, state, and local level. The communication that took place between these levels allowed women to share ideas and mobilize, such as through petitioning.

Gertrude Rush. Courtesy the Iowa Department of Human Rights’ Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame.

Gertrude Rush, a prominent lawyer from Des Moines, was a delegate to the 1912 Women’s Convention. There, she spoke and listed many of the reasons African American women needed the vote. She said the vote would provide African American women “better working conditions, higher wages, and greater opportunities in business.” Mrs. Rush also thought that through their votes African American women would end discrimination, lynching, and legal injustice, such as a lack of access to property rights.

Mobilizing to Win Elections

The 1924 presidential election was one of the first in which African American women had a direct impact on the outcome.

African American women organized their political activity within clubs and associations. Many of these clubs supported the Republican party and presidential incumbent Calvin Coolidge. The Republican party received widespread support from African Americans because it had delivered Emancipation from slavery and the vote to African American men.

Sue M. Wilson Brown. Courtesy the Iowa Department of Human Rights’ Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame.

In August of 1924 the National League of Republican Colored Women (NLRCW) was formed. Sue M. Wilson Brown, a suffragist and active leader from Iowa, was vice-president of this organization. According to historian Evelyn Brooks Higgenbotham, the officers of the NLRCW were “well known for their visibility in political affairs and for their work for the NAACP and the Urban League.”

African American women used many tools in their efforts to encourage participation in the election. In Iowa the women were unique for using the telephone in the get-out-the-vote drive. Coolidge was elected to a second term.

The longstanding support for the Republican party from African Americans ended during the Great Depression. This was due to the failure of president and Iowa native Herbert Hoover to address the economic and civil rights conditions of African Americans. Many African Americans saw Franklin D. Roosevelt’s proposed “New Deal” as a path toward opportunity.

Universal Suffrage: The Vote For All

The first page of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Courtesy the National Archives.

“No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

The ratification of the 19th amendment in 1920 established sexual equality in the right to vote. It failed to address the state laws, mainly in the southern United States, that prevented African Americans from exercising their right to vote.

In these states, white women gained the right to vote but African American women did not. It was not until 1965 and the passage of the Voting Rights Act that universal suffrage—the right of every woman and man, African American and white—was achieved.

Today, voting rights remain under threat. Laws that require a photo ID to vote, gerrymandering of voting districts, removing people from the voting rolls, and the courts striking down parts of the Voting Rights Act, have all had a negative effect on some Americans’ right to vote.

Today millions of women live in states where their grandmothers and great grandmothers did not have the right to vote a century ago. While African American women’s voting rights were hard won, full equality is not yet achieved.